Motor nuclei of cranial nerves VII (facial), V (trigeminal), and XII (hypoglossal) supply the cranial muscles that are most commonly tested in an electromyography (EMG) laboratory. In the caudal pons, the facial motor nucleus gives rise to the efferent fibers that form the facial nerve. This nerve supplies the muscles of facial expression, platysma, posterior belly of the digastric, and the stylo-hyoid (Gray’s Anatomy, 1977). The intrapontine portion of the facial nerve initially projects posteriorly to loop around the sixth nerve (abducens) nucleus. The long intrapontine course makes it vulnerable to various brainstem lesions, which cause a peripheral rather than central type of facial palsy. The facial nerve emerges from the brainstem near the caudal border of the pons, at the cerebellopontine angle. At this site the nerve is prone to injury by acoustic neuromas or other cerebellopontine angle masses. After traversing the subarachnoid space, the facial nerve enters the internal auditory meatus. Here it begins the long and complex intraosseous course through the petrous portion of the temporal bone (facial canal). Within this segment lies the presumed site of the lesion in Bell’s palsy. The facial nerve then exits the skull at the stylomastoid foramen and courses anteriorly to penetrate the superficial and deep lobes of the parotid gland. At this site the nerve is vulnerable to injury by parotid tumors and blunt trauma. Other etiologies of facial nerve dysfunction include meningitis, borreliosis, tuberculosis, herpes zoster, AIDS, and sarcoidosis. A lesion involving facial motor neurons or fibers of the facial nerve within the brainstem or in their peripheral course produces paralysis of facial movements. The particular deficit that results depends on the exact location of the lesion and its extent fora review see Carpenter, 1976). In clinical practice, EMG of facial muscles is most commonly performed in patients with suspected Bell’s palsy or in those with traumatic injury to the facial nerve.

The motor nucleus of the trigeminal nerve, located in the midpons of the brainstem, gives rise to the efferent fibers that innervate the muscles of mastication (masseter, temporalis, and pterygoids), mylohyoid, anterior belly of the digastric, and the tensor tympani and tensor veli palatini. The motor fibers emerge from the brainstem near the lateral border of the pons and exit the skull through the foramen ovale. Together with the corresponding sensory fibers, they form the mandibular division of the trigeminal nerve, which is distributed to the above-mentioned muscles. In practice, needle EMG of the muscles of mastication is most commonly performed in patients with suspected trigeminal nerve injury. Injury to the trigeminal nerve occurs with trauma (gun shot or stab wounds), surgery, infections (meningitis, borreliosis, tuberculosis, herpes zoster, and AIDS), sarcoidosis, acoustic neuromas, invasive tumors of the head and neck, and aneurysms. Clinical features of a trigeminal nerve lesion include numbness or loss of sensation over the face and weakness of closing of the jaw.

The hypoglossal nerve is a motor nerve that supplies the complex musculature of the tongue. The neuronal cell bodies that give rise to the nerve are found in the dorsal medulla of the brainstem in the hypoglossal neucleus. The nerve exits the cranium via the hypoglossal canal at the base of the skull. Injury to the hypoglossal nerve occurs with fractures of the base of the skull, tumors of the skull base, and aneurysms of the carotid artery. Hypoglossal nerve injury produces a lower motor neuron paralysis of the ipsilateral half of the tongue. Clinical signs include loss of movement, loss of tone, atrophy of muscle, and involuntary muscle twitches (i.e., fasciculations). Since the major muscle of the tongue, the genioglossus, controls protrusion of the tongue, a unilateral hypoglossal nerve injury will cause the protruded tongue to deviate to the side of the lesion. In practice, EMG of tongue muscles is often performed in patients with suspected motor neuron disease (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis).

Anatomical Illustrations

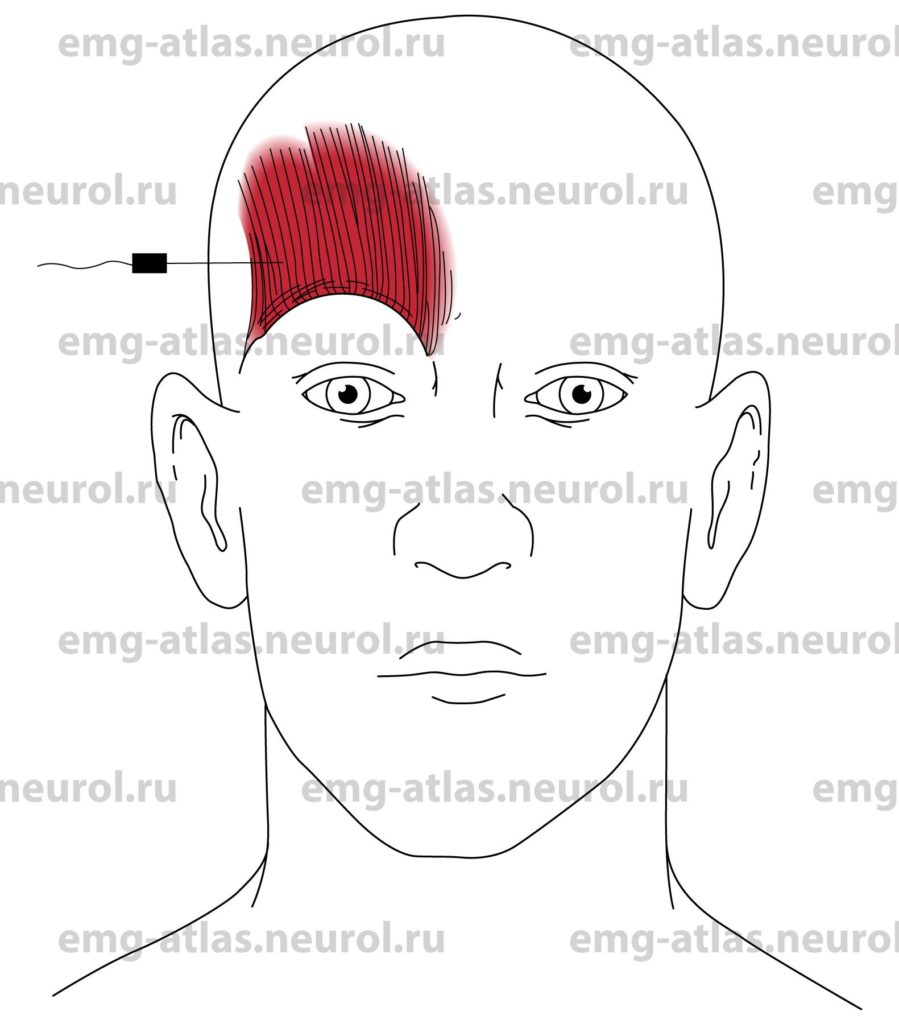

Frontalis

Innervation

Innervation is via cranial nerve VII (facial nerve).

Origin

The frontalis originates at the aponeurosis below the coronal suture.

Insertion

The fibers form a broad, thin, flat layer on the frontal scalp that merges with fibers from the orbicularis oculi and other facial muscles.

Activation Maneuver

Gentle raising of the eyebrows activates the muscle.

EMG Needle Insertion

Insert the needle at a 20 to 30 degree angle with the skin, 2 cm superior to the lateral half of the orbital margin.

Pitfalls

Do not insert the needle perpendicular to the skin. The muscle is very thin, and the needle must remain superficial.

Clinical Comments

Needle examination of facial muscles is usually performed in patients with suspected Bell’s palsy or other injury to the facial nerve.

Neurogenic EMG changes (i.e., increased insertional activity, fibrillation potentials, excessive polyphasic motor unit potentials) occur when injury to the facial nerve or facial nucleus produces axonal loss.

Anatomical Illustrations

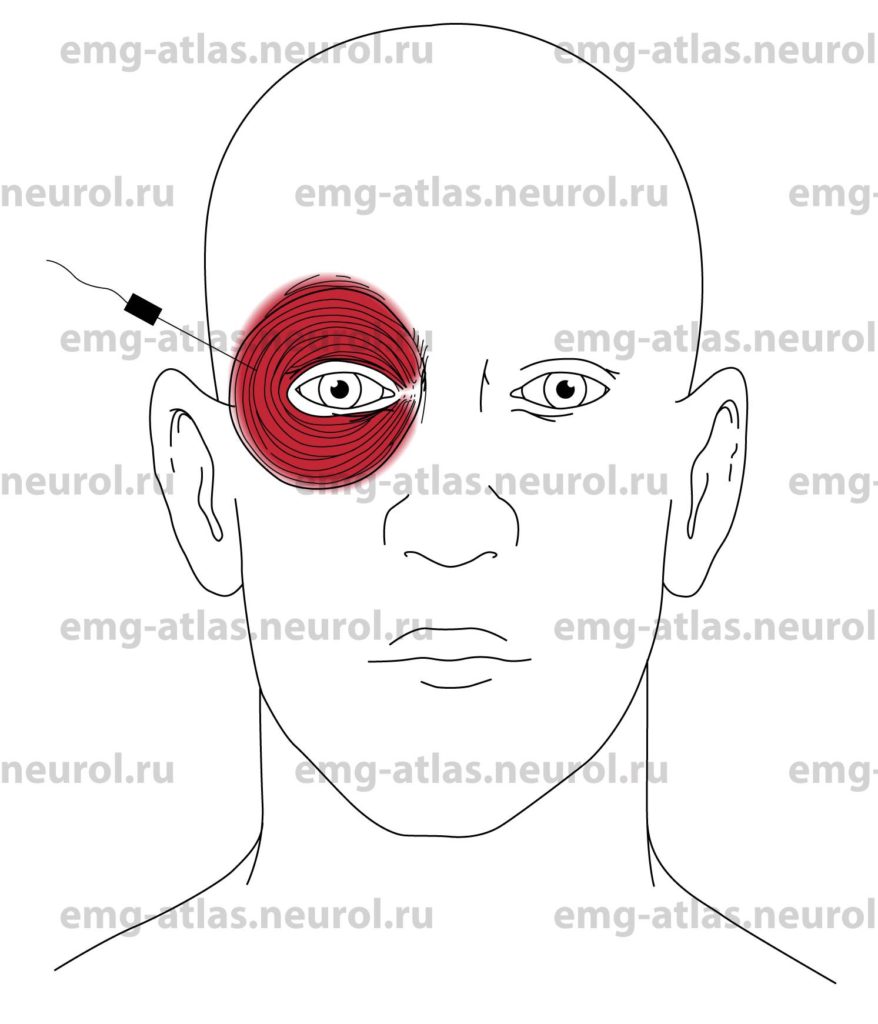

Orbicularis Oculi

Innervation

Innervation is via cranial nerve VII (facial nerve).

Origin

The orbicularis oculi is a sphincter muscle that surrounds the orbit and eyelids (Gray’s Anatomy, 1977). It arises from the frontal and maxillary bones.

Insertion

The fibers are directed outward, forming a broad, thin, flat layer that surrounds the orbit and eyelids.

Activation Maneuver

Gentle eye closure or blinking activates the muscle.

EMG Needle Insertion

Insert the needle at a 20 to 30 degree angle with the skin, lateral to the outer wall of the orbit, which is formed by the malar bone.

Pitfalls

Do not insert the needle perpendicular to the skin. The muscle is very thin, and the needle must remain superficial.

Excessive motion of the needle may result in hemorrhage («black eye»).

Clinical Comments

Needle examination of facial muscles is usually performed in patients with suspected Bell’s palsy or other injury to the facial nerve.

Neurogenic EMG changes (i.e., increased insertional activity, fibrillation potentials, and excessive polyphasic motor unit potentials) occur when injury to the facial nerve or facial nucleus produces axonal loss.

Anatomical Illustrations

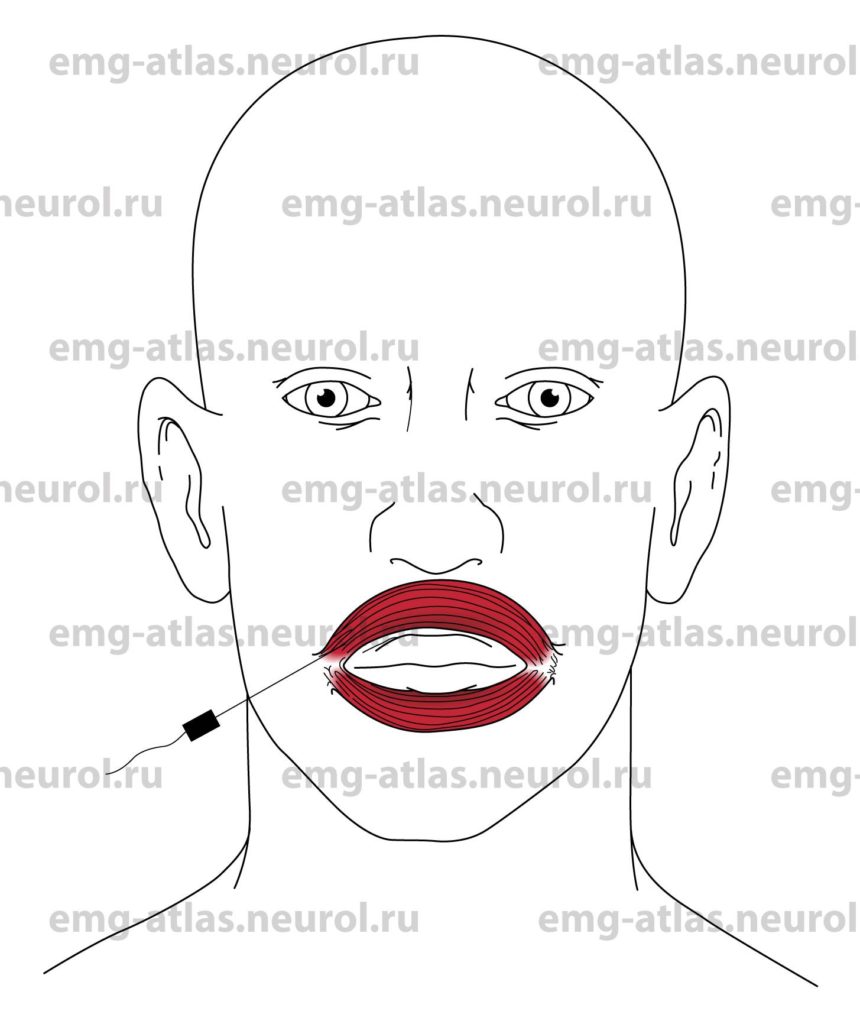

Orbicularis Oris

Innervation

Innervation is via cranial nerve VII (facial nerve).

Origin

The orbicularis oris consists of numerous strata of muscular fibers, having different directions, which surround the orifice of the mouth (Gray’s Anatomy, 1977). These fibers are partially derived from other facial muscles that insert into the lips and partly from fibers proper to the lips themselves.

Insertion

There is no single point of insertion.

Activation maneuver

Gentle puckering of the lips activates the muscle.

EMG Needle Insertion

Insert the needle at a 20 to 30 degree angle with the skin, just lateral to the angle of the mouth.

Pitfalls

Do not insert the needle perpendicular to the skin. The muscle is thin, and the needle may penetrate the oral cavity.

Clinical Comments

Needle examination of facial muscles is usually performed in patients with suspected Bell’s palsy or other injury to the facial nerve.

Neurogenic EMG changes (i.e., increased insertional activity, fibrillation potentials, and excessive polyphasic motor unit potentials) occur when injury to the facial nerve or nucleus produces axonal loss.

Anatomical Illustrations

Masseter

Innervation

Innervation is via the motor nucleus of cranial nerve V (trigeminal nerve).

Origin

The masseter originates from the malar process of the superior maxilla and the lower border of the zygomatic arch (Gray’s Anatomy, 1977).

Insertion

Insertion is into the angle of the jaw, outer surface of the ramus, and coronoid process of the jaw.

Activation Maneuver

Jaw closure activates the muscle.

EMG Needle Insertion

Insert the needle 2-3 cm distal to the angle of the jaw and 2 cm cephalad to the lower edge of the mandible (the muscle belly is easily palpated when the patient clenches the teeth).

Pitfalls

If the needle is inserted too posteriorly, it may penetrate the parotid gland or duct that overlaps the posterior margin of the muscle.

If the needle is inserted too anteriorly, it may penetrate the buccinator muscle supplied by the facial nerve) that lies beneath the anterior margin of the masseter muscle.

Clinical Comments

Needle examination of the masseter muscle is usually performed in patients with suspected injury to the trigeminal nerve.

Neurogenic EMG changes (increased insertional activity, fibrillation potentials, and excessive polyphasic motor unit potentials) occur when injury to the trigeminal nerve or motor nucleus produces axonal loss.

Anatomical Illustrations

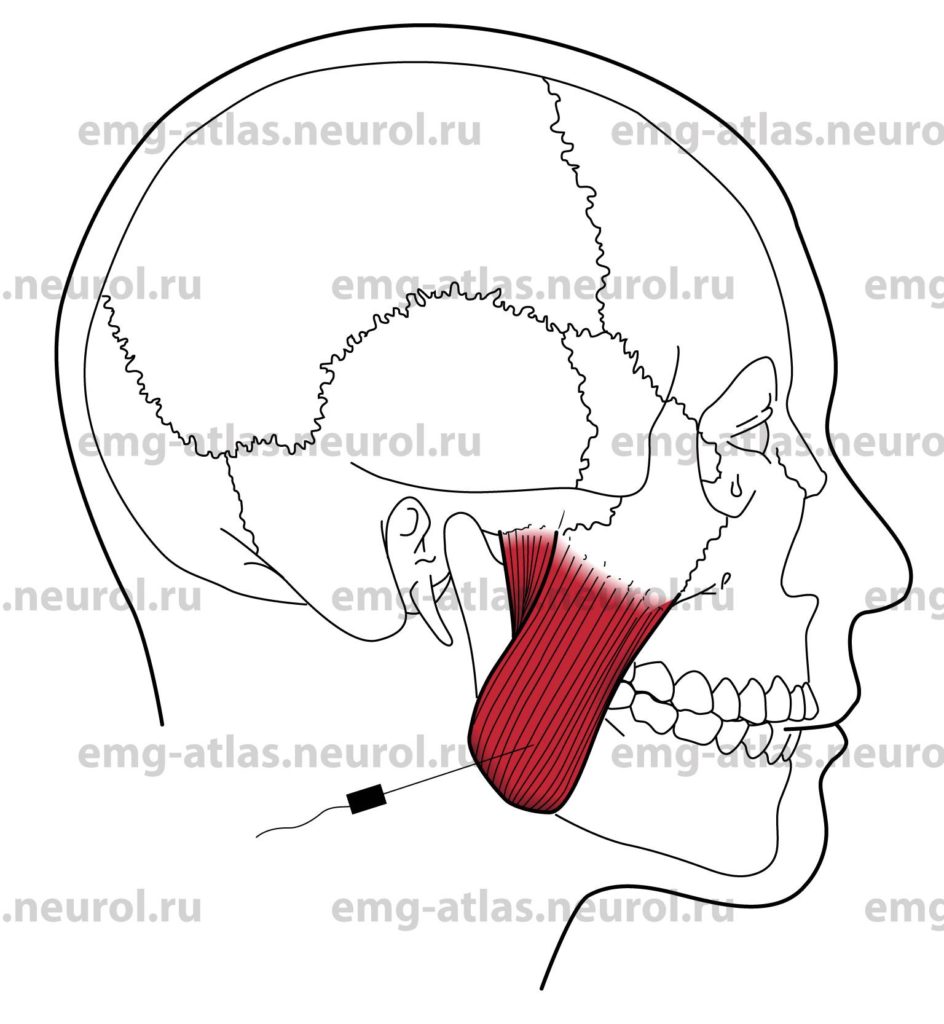

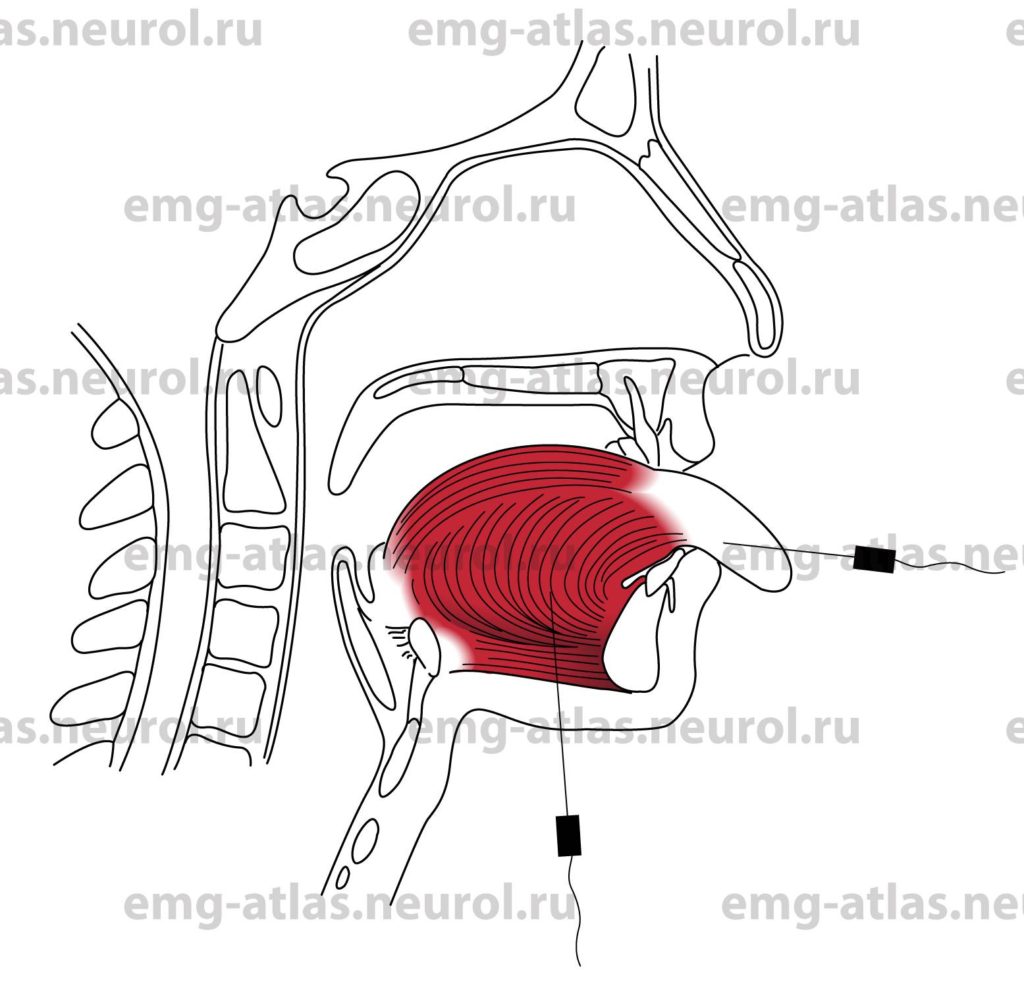

Tongue

Innervation

Innervation is via cranial nerve XII (hypoglossal).

Origin

The tongue is composed of muscular fibers from multiple muscles arranged in various directions (Gray’s Anatomy, 1977).

This complex arrangement of the muscular fibers, and the various directions in which they run, give the tongue the ability to assume the various forms necessary for enunciating the different consonantal sounds.

The major muscle of the tongue, the genioglossus, arises from the superior genial tubercle on the inner side of the symphysis of the jaw.

Insertion

The genioglossus muscle spreads out in a fanike form. The inferior fibers attach to the body of the hyoid bone, and the middle and superior fibers pass backward, upward, and then forward to enter the whole length of the undersurface of the tongue.

Activation Maneuver

Gentle protrusion of the tongue activates the muscle. Deviation away from the needle generates muscle activity.

EMG Needle Insertion

Insert the needle into the midline undersurface of the mandible 2-3 cm posterior to the tip of the chin. The needle may be angled to study the right or left genioglossus muscle.

Alternatively, the examiner can grasp the tongue with a gauze pad and insert the needle into the inferolateral portion of the tongue. To study spontaneous activity, ask the patient to gently retract the tongue so that it lies on the floor of the oral cavity.

Pitfalls

This study requires patient cooperation.

Clinical Comments

Needle examination of the tongue is often performed in patients with suspected amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

Neurogenic changes (increased insertional activity, fibrillation potentials, and excessive polyphasic motor unit potentials) occur when injury to the hypoglossal nerve or nucleus produces axonal loss.