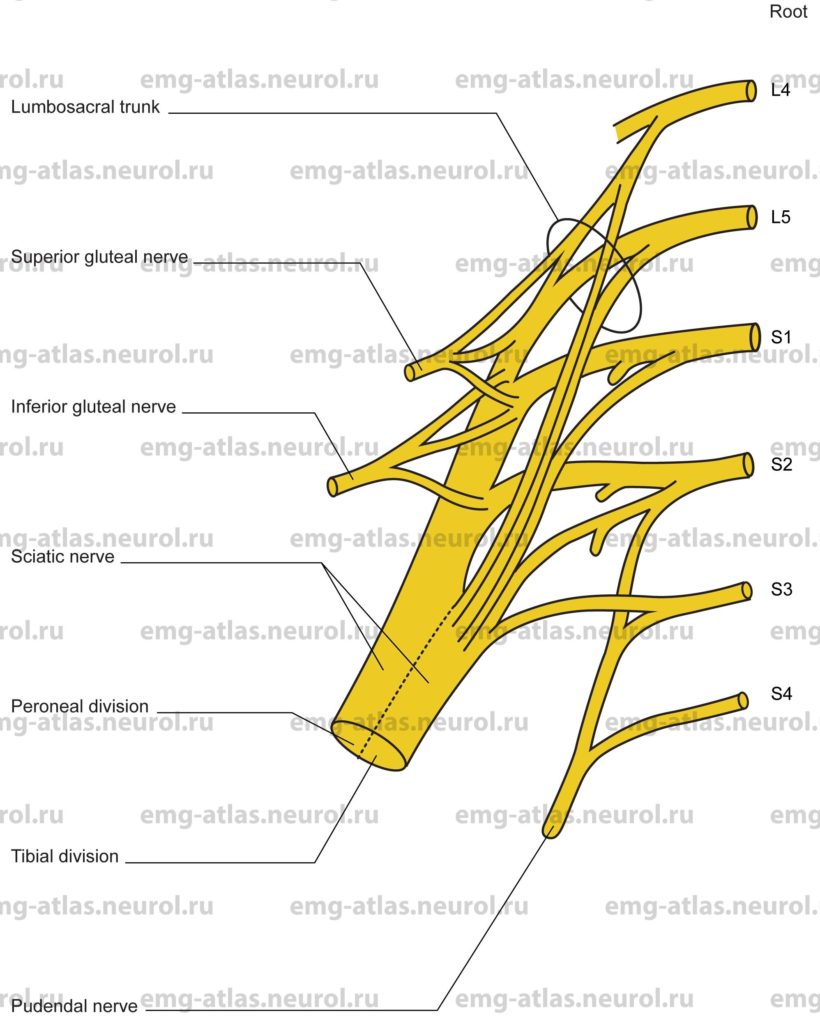

Diagram of the sacral plexus (anterior view) and its branches.

The sacral plexus is formed by the lumbosacral trunk (a small branch of the fourth lumbar ventral ramus that joins the fifth lumbar ventral ramus), the first through third sacral ventral rami, and part of the fourth ventral ramus (Gray’s Anatomy, 1995). It adjoins the posterior pelvic wall anterior to the piriformis muscle and posterior to the internal iliac vessels, ureter, sigmoid colon, and terminal ileum.

Pelvic fascia separates the sacral plexus from the viscera of the pelvis. The upper rami proceed obliquely downward and outward, while the lower rami proceed nearly horizontally. All rami converge toward the greater sciatic foramen and unite to form two cords, an upper, larger one and a lower, smaller cord. The upper, larger cord is formed by the lumbosacral trunk (L4, L5) and the first (S1), second (S2), and part of the third (S3) sacral ventral rami. This cord becomes the sciatic nerve. The lower, smaller cord is formed by portions of the second (S2), third (S3), and fourth (S4) sacral ventral rami. This becomes the pudendal nerve. In addition, the sacral plexus can be divided into anterior and posterior divisions, with the tibial portion of the sciatic nerve formed by the anterior division and the peroneal portion formed by the posterior division.

Branches of the sacral plexus include muscular branches to the quadratus femoris and gemellus inferior (L4, L5, S1), the obturator internus and gemellus superior (L5, S1, S2), and the piriformis (S1, S2). Note the short muscles around the hip joint — quadratus femoris, gemellus superior, gemellus inferior, obturator internus, obturator extemus (this muscle is supplied by the lumbar plexus via the obturator nerve), piriformis, and pectineus (this muscle is supplied by the lumbar plexus via the femoral nerve) — are largely innaccessible to direct observation. Because of the potential complications presented by their intimate relationship with important neurovascular structures, there is a total lack of EMG data in humans (Gray’s Anatomy, 1995). Muscular branches also supply the levator ani, coccygeus, sphincter ani extemus (S4), and pelvic splanchnic nerves (S2, S3, S4). The sacral plexus also gives rise to the superior gluteal nerve (L4, L5, S1), which supplies the gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, and tensor fasciae latae; the inferior gluteal nerve (L5, S1, S2) to the gluteus maximus; the posterior cutaneous nerve of the thigh (S1, S2, S3); and the perforating cutaneous nerve (S2, S3).

A lesion of the sacral plexus produces a clinical picture similar to that seen with a sciatic nerve lesion, but with additional involvement of the gluteal muscles, tensor fasciae latae, and, occasionally, the anal sphincter.

Sacral Plexus Lesion

Etiology

Tumors and metastatic lesions can cause a sacral plexus lesion. Malignant infiltration is the most common cause of involvement of the lumbosacral plexus, usually due to spread of carcinoma of the cervix, uterus, prostate, or rectum (Gray’s Anatomy, 1995).

Neuralgic amyotrophy (also known as idiopathic lumbosacral plexopathy, acute idiopathic mononeuropathy, or lumbosacral plexus neuropathy; (Kimura, 1989) is causative.

Trauma, including pelvic fractures, stab wounds, or gunshot wounds, can cause a sacral plexus lesion.

Traction injury during orthopedic or other surgical manipulation (common during hip joint replacement) can cause a sacral plexus lesion.

Radiation plexopathy is causative.

Compression plexopathy occurs due to retroperitoneal hematomas, usually in hemophiliacs, in those with coagulopathies, or during anticoagulation therapy.

Compression lesions against the bony pelvis also occur and affect the common peroneal fibers maximally or exclusively. The greater vulnerability of the peroneal fibers is due, in part, to the more direct relationship of the posterior division, which comprises peroneal fibers, with the bony pelvis Sunderland, 1968).

General Comments

Malignant infiltration usually gives rise to painful and slowly progressive paralysis unilaterally (Kimura, 1989).

Radiation plexopathy causes very slowly progressive, painless leg weakness, often bilateral.

Neuralgic amyotrophy is characterized by acute pain in one or both legs that precedes the onset of weakness and areflexia.

Clinical Features

The distribution of weakness is similar to that seen with a sciatic nerve lesion.

There can be additional weakness of the gluteal muscles, tensor fasciae latae, or anal sphincter.

Wasting of lower limb muscles occurs.

Numbness occurs over the posterior thigh, lateral half of the leg, and entire foot.

There is an absent or reduced Achille’s stretch reflex.

Electrodiagnostic Strategy

Use nerve conduction studies to confirm a lesion involving the sacral plexus low amplitude or unelicitable sensory responses from sural and superficial peroneal nerves and low amplitude or unelicitable motor responses from tibial and peroneal nerves). Sensory responses are normal in radiculopathies because the lesion is proximal to the dorsal root ganglion (preganglionic lesion) and the cell bodies in the ganglion maintain viability of the peripheral sensory fiber.

Demonstrate neurogenic EMG needle examination (i.e., spontaneous activity, abnormal motor unit potentials, and abnormal recruitment) in muscles supplied by the sacral plexus.

Use needle EMG to exclude lumbosacral radiculopathies. Radiculopathies produce neurogenic findings in paraspinal muscles as well as in limb muscles; plexopathies never do so because the plexus is formed by ventral rami, whereas paraspinal muscles are innervated by posterior rami (Wilbourn, 1985).