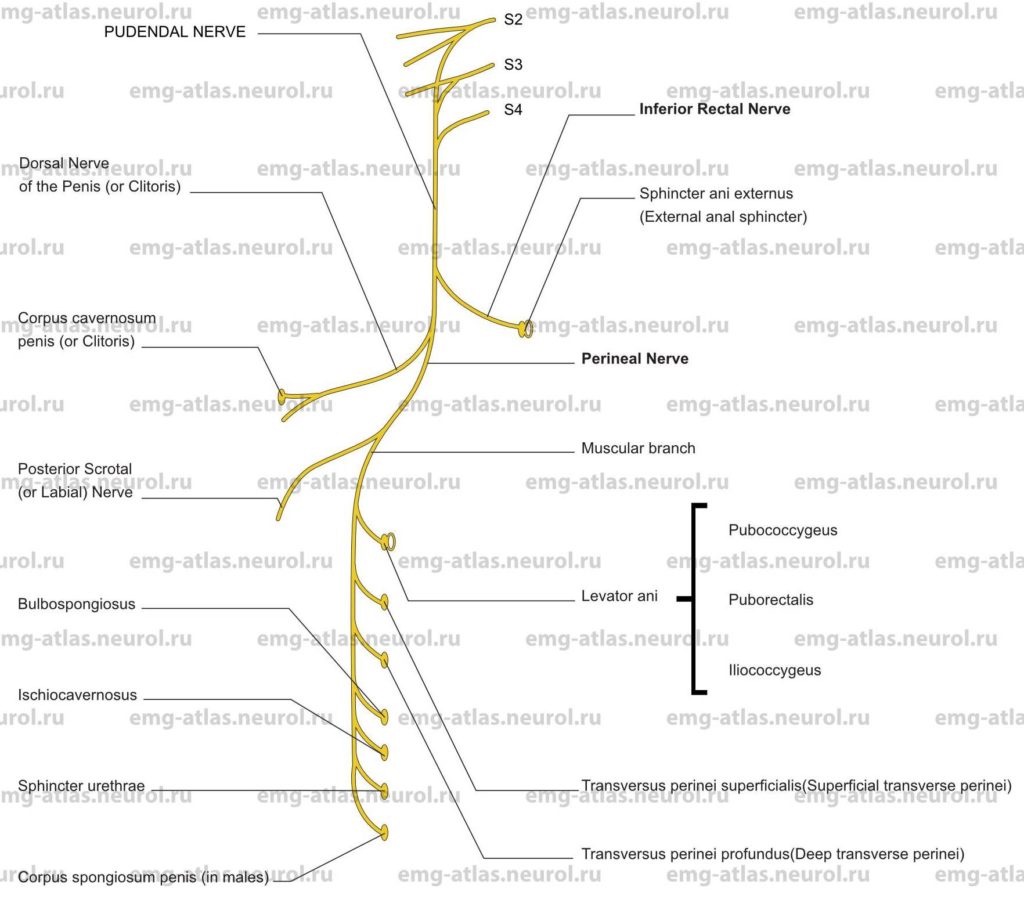

Diagram of the pudendal nerve and its branches. NOTE: The white ovals signify that a muscle receives part of its innervation via direct branches from the sacral plexus.

The pudendal nerve is the direct continuation of the lower band of the sacral plexus and is derived from the second, third, and fourth sacral ventral rami. It leaves the pelvis via the greater sciatic foramen below the piriformis to enter the gluteal region. It then crosses the spine of the ischium and re-enters the pelvis through the lesser sciatic foramen. It accompanies the internal pudendal artery through the lesser sciatic foramen, passing into the pudendal canal (Alcock’s canal) on the lateral wall of the ischiorectal fossa. In the posterior part of the canal it gives off the inferior rectal nerve. It then divides into two terminal branches, the perineal nerve and the dorsal nerve of the penis (or clitoris). In about 20% of subjects, the inferior rectal nerve arises directly from the sacral plexus (Gray’s Anatomy, 1995).

The inferior rectal nerve pierces the medial wall of the pudendal canal, crosses the ischiorectal fossa with the inferior rectal vessels, and supplies the sphincter ani extemus (external anal sphincter), the lining of the lower part of the anal canal, and the skin around the anus. The perineal nerve, the inferior and larger terminal branch of the pudendal nerve, runs forward with the perineal artery, dividing into posterior scrotal (or labial) nerve and muscular branches. The posterior scrotal or labial nerve connects with cutaneous branches of the inferior rectal nerve and posterior femoral cutaneous nerve to supply scrotal or labial skin. The muscular branches supply the anterior portions of the levator ani and the external anal sphincter, transversus perinei superficialis (superficial transverse perinei), transversus perinei profundus (deep transverse perinei), bulbospongiosus, ischiocavemosus, and sphincter urethrae. In males, a branch also supplies the corpus spongiosum penis. The muscles of the pelvic floor, in particular the levator ani, also receive direct innervation from branches of the second, third, and fourth sacral nerves. This is an important concept because pudendal nerve injury does not necessarily cause dysfunction in the muscles of the pelvic floor (Retzky et al., 1996). The dorsal nerve of the penis is the deepest division of the pudendal nerve. It supplies the corpus cavemosum penis and passes forward to provide sensation to the dorsum of the penis. In females the homologous dorsal nerve of the clitoris is very small.

Electrophysiologically, the muscles of the pelvic floor differ from most other skeletal muscles in that they exhibit constant EMG activity except during voiding and defecation (Retzky et al., 1996). The tonic activity in these muscles is necessary to continually support the viscera in the pelvic cavity.

Injury to the muscles or nerves of the pelvic floor often occurs during parturition. A tear involving the perineal body and perivaginal musculature may result in uterovaginal prolapse. This may often be prevented by incising the perineum (episiotomy) to provide a clean, easily reparable wound. Fecal incontinence due to anal sphincter damage or to a rectovaginal fistula may also occur following vaginal delivery or extension of a midline episiotomy (Fleshman, 1996).

Pudendal Nerve Lesion

Etiology

Vaginal delivery (usually associated with third or fourth degree perineal tears) can cause a pudendal nerve lesion.

Pelvic tumors, including the delayed effects of pelvic radiation therapy, can be causative.

Other causes of pudendal nerve lesions are (1) iatrogenic (pelvic surgery), (2) blunt pelvic trauma or penetrating injures, (3) compression of the perineal branches during bicycle riding, and (4) chronic stretch injury, usually seen with repeated and excessive straining during defecation (Dominguez and Saclarides, 1996).

General Comments

The most common cause of injury to the pudendal nerve or to its branches is parturition. Damage occurs by mechanical disruption of muscle fibers or disruption of the innervation to skeletal muscle.

Conus medullaris or cauda equina injury may damage the anterior horn cells or sacral roots, which are the source of the pudendal nerve and sacral nerves that supply muscles of the pelvic floor.

Clinical Features

Fecal incontinence can occur due to anal sphincter disruption during delivery often associated with extension of a midline episiotomy).

Passage of flatus or stool through the vagina (rectovaginal fistula) can occur due to obstetric injury.

Numbness or loss of sensation can occur in the perineal region.

Vaginal vault prolapse may be related to partial denervation of pelvic floor muscles during delivery (Timmons and Addison, 1996).

Impotence can occur. The bulbospongiosus assists in penile erection by compressing erectile tissue of the bulb and by compressing the deep dorsal vein of the penis. The ischiocavernosus maintains penile erection by compressing the crus penis.

Urinary incontinence can occur. The sphincter urethrae surrounds not only the lower urethra but also the bladder neck It compresses the urethra, particularly when the bladder is full, to voluntarily delay voiding.

Weakness and atrophy of the muscles of the pelvic floor occur, resulting in loss of support of the viscera in the pelvic cavity.

Electrodiagnostic Strategy

Use nerve conduction studies (pudendal nerve terminal motor latency) to evaluate a lesion of the pudendal nerve or its branches. Techniques have been developed for recording terminal motor latencies from both the inferior rectal branch and the perineal branch (Benson and Brubaker, 1996).

Pudendal somatosensory evoked potentials can evaluate pudendal sensory pathways.

Perform EMG needle examination in muscles innervated by the pudendal nerve or its branches. In pudendal nerve lesions associated with loss of motor fibers, EMG may show neurogenic changes (i.e., fibrillation potentials, polyphasic motor unit potentials, and neurogenic recruitment).

If EMG of the pelvic floor muscles is abnormal and if the etiology is not clearly obstetric, study the muscles innervated by other sacral roots to exclude cauda equina or sacral root involvement (i.e., abductor hallucis, medial gastrocnemius, and paraspinal muscles).

Anatomical Illustrations

Sphincter Ani Externus (External Anal Sphincter)

Innervation

Innervation is via the inferior rectal branch, pudendal nerve, sacral plexus, and roots S2, S3.

There is also, a direct branch from the sacral plexus and root S4.

Origin

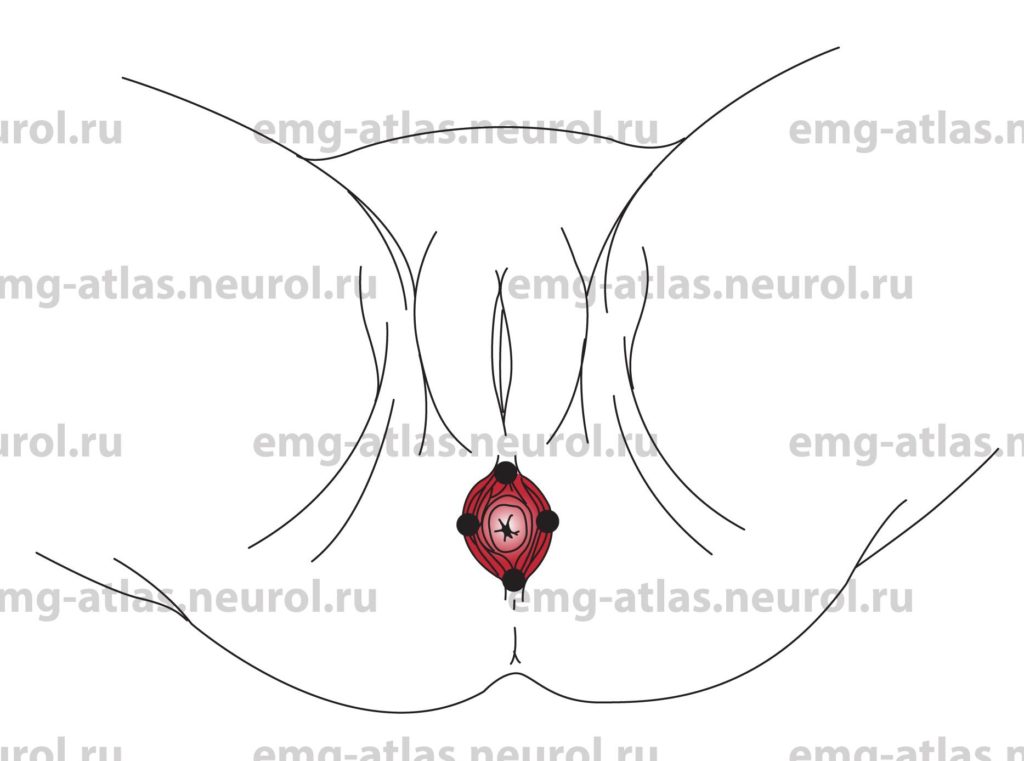

The external anal sphincter is a tube of skeletal muscle with deep, superficial, and subcutaneous layers that surround the whole anal canal.

Insertion

Fibers from deep, superficial, and subcutaneous parts attach anteriorly to the perineal body and posteriorly to the coccyx.

Some fibers blend with the puborectalis or attach to the superficial transverse perineal muscles and to the anococcygeal raphe.

Activation Maneuver

This muscle exhibits constant EMG activity that keeps the anal canal closed except during defecation. To assess spontaneous activity such as fibrillation potentials, ask the subject to bear down as if having a bowel movement. To maximally activate the muscle, ask the subject to tighten or contract the anal sphincter.

EMG Needle Insertion

Insert the needle into the external anal sphincter at the 12:00, 3:00, 6:00 and 9:00 clock positions with the patient in the lithotomy position. This evaluation should ideally be performed with the gynecological surgeon present, particularly if surgery is planned to repair mechanical disruption of the muscle fibers or disruption of the innervation to the muscle.

The presence or absence of insertional activity in different segments of the muscle reflecting the presence or absence of viable skeletal muscle) and the inability to voluntarily contract portions of the muscle are crucial information for the surgeon.

Pitfalls

There are no pitfalls. The examiner should not insert his or her finger into the anus to guide the needle examination. This practice is unnecessary and poses a risk of needle injury to the examiner.

Clinical Comments

Neurogenic changes on needle examination may be seen with lesions of the inferior rectal nerve, pudendal nerve, sacral plexus, or S2, S3, S4 roots.

Anatomical Illustrations

Levator Ani

Innervation

Anteromedial portion: Innervation is via the perineal nerve, pudendal nerve, sacral plexus, and roots S2, S3, S4.

Posterolateral portion: Innervation is via the direct branches from sacral plexus, and roots S2, S3, S4.

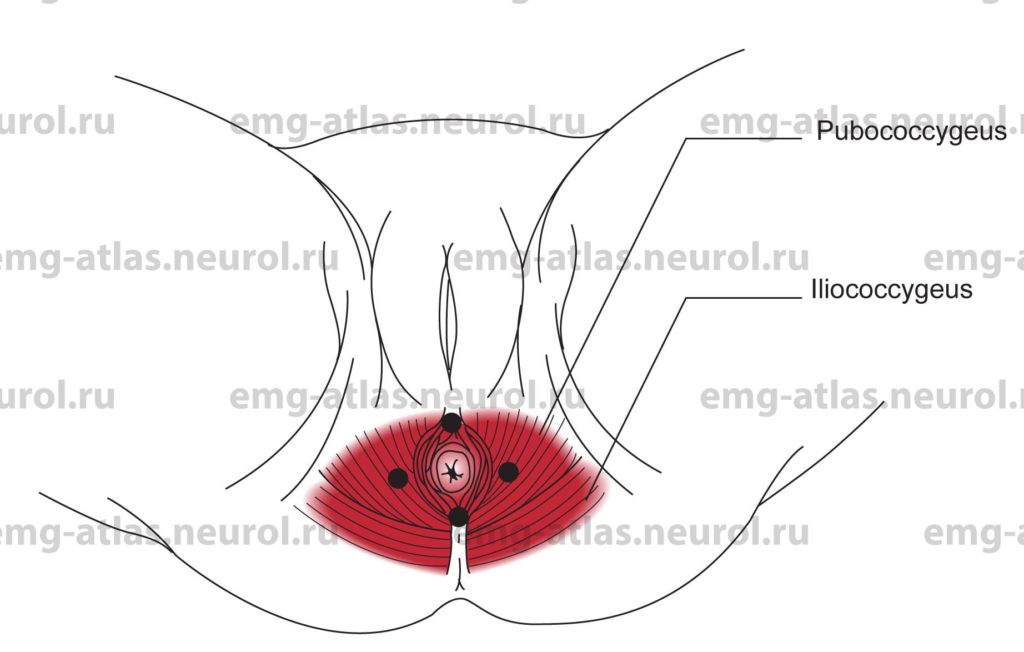

Origin

The levator ani is a broad muscular sheet that forms the floor of the pelvic cavity. Right and left counterparts unite to support the viscera in this cavity and to surround the various structures that pass through it. The levator ani is separated into three muscular parts: pubococcygeal part (pubococcygeus), puborectal part puborectalis), and iliococcygeal part (iliococcygeus).

The pubococcygeus arises from the back of the body of the pubis and passes back horizontally. The fibers form part of the periurethral, perivaginal, and perirectal musculature.

The puborectalis arises from the back of the body of the pubis (inseparable from the pubococcygeus at its origin) and joins its fellow muscle from the opposite side to form a sling around the anorectal junction.

The iliococcygeus arises from the obturator fascia between the obturator canal and the ischial spine.

Insertion

Most fibers of the pubococcygeus attach to the anterior surface of the coccyx. Some fibers insert into the walls of the vagina, perineal body, and rectum.

The puborectalis joins its fellow muscle from the opposite side to form a sling around the anorectal junction.

The iliococcygeus attaches to the sides of the last two segments of the coccyx.

Activation Maneuver

Muscles exhibit constant EMG activity and contribute to bowel and bladder continence; they must relax to permit voiding and defecation (Retzky et al., 1996). To assess spontaneous activity such as fibrillation potentials, ask the subject to bear down as if having a bowel movement. To maximally activate the muscle particularly the puborectalis), ask the subject to tighten the anal sphincter.

EMG Needle Insertion

Puborectalis: Insert the needle into the posterior half of the external anal sphincter to a depth of 2-3 cm. The puborectalis lies deep to the external anal sphincter and is separated from it by a thin layer of fat and connective tissue that results in loss of insertional activity on needle examination.

Pubococcygeus: Insert the needle 1-2 cm on either side of the external anal sphincter. The pubococcygeus is the only muscle encountered.

Iliococcygeus: This muscle is thin, aponeurotic, and not easily accessible by routine needle examination.

Pitfalls

If the needle is inserted too deeply, it may penetrate the rectum and peritoneum.

Clinical Comments

Neurogenic changes on needle examination may be seen with lesions of the perineal nerve, pudendal nerve, sacral plexus, or S2, S3, S4 roots.